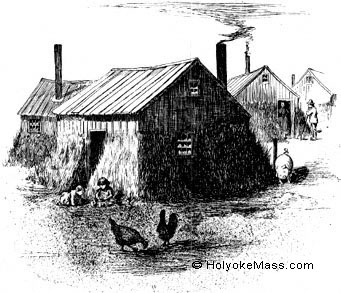

The two societies continued to work together until 1834, when the Congregationalists put up a building of their own at the village, a mile north of Elmwood. There it stands to this day, and though for the last few years it has served for a tenement, and has lost its bell-tower and is otherwise altered, it still retains a churchly look, and with the old tavern and a few houses close at hand, is about the only memorial of the days of Ireland Parish. Until 1849, when the Second Congregational church was built, down on High street, an omnibus was regularly run from the village, by the river, to convey the worshipers of that vicinity to the church on Northampton street. With the advent of the new society in the lower village, there was such a decrease in the congregation of the old church, and so great a falling off in the financial support, that considerable discouragement followed, and it was many years before the society recovered itself. At the time the project of building a dam across the Connecticut was first thought of, the manufacturing industries of the place consisted of a little cotton mill, three stories in height—now the lower part of the Parsons’ finishing room—and a small wooden, two-story gristmill, whose upper floor was used as a dressing-room for the cotton used in the other mill. A wind wall a hundred and fifty feet in length was built diagonally upstream, out into the current of the ricer, and turned the water into the little canal, which was barely twenty feet across. This wing wall was about where the present dam is. The gristmill stood where the Mt. Tom mill now is, and the cotton mill was close below, both built right on the river bank. In front of the cotton mill was a row of three two-story, brick boarding-houses, and just above them was a small brick store. All this property was owned by the mills which were controlled by Smith Brothers of Enfield. The help in the mills was at that time, almost without exception, native American, drawn from the farming communities about, and this was the case all through New England during the first two decades of its manufacturing enterprise. Near the mills were four or five farmhouses, and on the flat below them were several more. All this region was commonly known as "The Field" was, in the main, clear of trees, and was used for mowing and tillage. There were two little swales near the depot, but otherwise it furnished fairly good meadow land. Depot hill was well wooded, and a patch of woodland of perhaps thirty or forty acres extended from here to the river, south of the old ferry landing. This was cut off just before the war. The slopes above the Field were given over to pastures mostly, but there was a big wood extending from South street up to Dwight street and westerly up to the cemetery. In the wood, near where William Whiting’s house now stands, was a little pond known as "Silver Lake," which was a famous place for frog concerts in the mist, spring evenings. It was a pleasant spot here to sit in the shade in the warm days of summer. In the winter, the youth of the region resorted thither to skate. Just above the junction of Dwight and High streets was a stretch of brushy, boggy land, where another company of frogs made music for the merchants who first built along High street. About the village, on Northampton street, were cultivated fields and orchards, and the big hillside beyond, to the west, was pasture land much as at present.

© Laurel O’Donnell 1996 - 2006, all rights reserved

This document may be downloaded for personal non-commercial use only and may not be reproduced or distributed without permission in any format. This is an edited adaptation from the original publication. |