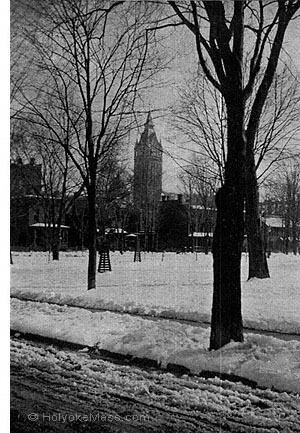

A Winter Picture — Hampden Park.

|

The shad fishery here was a mine of wealth in Holyoke’s village days, and he was a lucky man who owned a share in it. Some evening late in the winter, the members of the fish company would meet at Crafts’ tavern to organize for the coming year. There would fifteen or twenty men come together, and, having ordered a pitcher of flip, they proceeded to discuss business. The company drank several pitchers of this flip before it got through, a quantity which, if of modern liquor, would have been sure to produce serious results. But no one got drunk. The company became mellow and happy as the evening wore away, but still all could walk home straight. Flip was made in a large, brown stone pitcher. A dozen eggs and a pound of sugar was beaten together, a pint to a quart of "Old Santa Cruz rum" was added, and then such amount of water as was deemed to the company’s taste. Meanwhile the flip iron had been heating among the coals of the wide fireplace. It was pulled red hot from the fire, wiped, and plunged into the liquor, which, when it was sufficiently heated, was served steaming hot. The pitcher was passed about on a platter. There were no accompanying glasses, and each man drank from the pitcher. After it had gone the rounds, it was set on the shelf by the fire to keep warm. The business of the evening was to select a captain, a head seine man and a shore seine man, and a committee was appointed to calk the boat, to see to the net and mend it if need be, or perhaps to buy a new one.

As soon as the ice had gone out and the water began to catch the heat of the returning sun, the shad commenced to run. At sunrise some May morning the fish company gathered, the boat was slid into the river, and the fishing season had opened. There was no favorable fishing place along the shore on the Holyoke bank, and therefore a little island had been built somewhat out in the stream. The boat was poled up along the shore of this island to its upper end, where the "shore seine man" took his stand with one end of the net, while the head seine man commenced paying out the net piled in the bow of the boat as the craft swung out into the stream. The captain stood at the stern steering and giving orders as his men poled across the current, and allowed the boat presently to drop down stream, and finally brought it up at the foot of the island, having described a long loop in his course. Now all was excitement and hurry. The shore seine man had already brought his end of the net to the lower extremity of the island; out leaped the head seine man with the other end, and into the water went the whole crew to pull in the net and to hold down its lower edge to prevent the shad from darting beneath it. Two hundred was considered a big catch for a single haul in those days, but tradition handed down from days still more remote tells of taking in a single haul as many as two thousand. The shad when taken from the net were thrown into some big baskets, and these from time to time were conveyed to shore, where they were dumped into a broad, shallow box and exposed for sale. The farmers and peddlers would come from twenty miles around to purchase shad, and many families salted down a barrel or two for use in summer. Prices ranged from ten to twenty cents apiece, and a generation earlier had sold for six and eight cents. A salmon weighing five or six pounds was occasionally taken from the net, but this was rare. The shad themselves were handsome fish, weighing from three to six pounds, and were esteemed better eating than any steak, turkey or chicken.

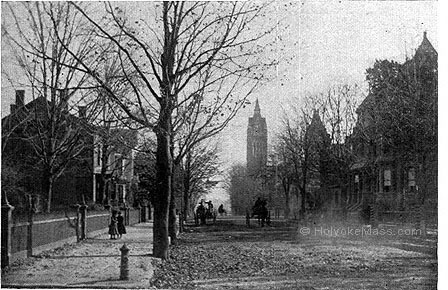

The City Hall from Dwight Street.

|

Prices of shad were quoted in the papers, and it was a common question along the road, “What’s a shad worth today?” A man could take a load up through Northampton, Williamsburg, Goshen, Conway, and Ashfield, and make eight or ten dollars in a day. Single families would often buy a dozen or two of them. At a convenient spot on the island, the fish company kept a bottle of Santa Cruz rum, which the members visited with more or less regularity. It is supposed that they drank just "enough to keep the wet out," as no one was ever known to get drunk. Fishing began at sunrise and it lasted until sunset, when the boat was brought to shore, the net reeled up, and the men were ready to scatter to their homes. First, however, receipts from the day’s sales and the fish left over were divided. To do this last, the following plan was adopted to secure perfect fairness. First the fish were laid onto as many piles as there were men, an equal number in each. Then the captain called forth one of the men, who turned his back upon the pile of fish, and as the captain pointed to each pile in turn he put to him this question, "Who shall have these?" And the man thereupon gave the name of some member of the company. Thus the piles were disposed of; each man took his share and was presently jogging homeward. There he sold some of them to neighbors and the rest he salted down.

The fishing season lasted somewhat over a month. Then the boat was drawn out of the water, and the net, after a few day’s drying, was stowed away in the fish house. At some time in the summer, when the water was low, a rope was dragged along the bottom of the fishing ground and the snags and rocks cleared out.

At night the shad dropped back from the falls to the quieter water below, and at Jed Day’s landing another company was ready to attack them. This company fished nights altogether.

© Laurel O’Donnell 1996 - 2006, all rights reserved

This document may be downloaded for personal non-commercial use only

and may not be reproduced or distributed without permission in any format.

This is an edited adaptation from the original publication.

|