WESTFIELD, THE "WHIP CITY."*

|

WHY WESTFIELD IS SO NAMED.—SOME ACCOUNT OF THE INGENUITY YOU BUY WHEN YOU BUY A WHIP.—AN ENTERTAINING HISTORY OF THE RISE OF THE BUSINESS AND WHAT HAS LED TO ITS PRESENT DEVELOPMENT.

|

Man with Whip.

|

In the beginning you will be inclined to exclaim: "Few things are so simple as a whip!" Not many articles of commerce have so ancient a lineage, though, that can be directly traced.

Of the thousands who buy whips to sell again, of the millions who buy whips to use, few are there among them who have the simplest comprehension of the processes involved in their manufacture.

A whip looks so simple when made that it is dismissed from further thought, as merely a whip!

If we go backward along the lines of the

HISTORY OF THE RACE

the record of Babylonian cylinders, Assyrian monuments, Egyptian tombs, Grecian bas-reliefs, Roman Parthenon friezes, and middle age art, all bear evidence to the use and importance of the whip in the unfolding of the life of the people of various countries.

But of whips, as of so many other things, it was left to American genius to evolve a rude, simple thing into a highly organized product, requiring capital, machinery and skilled labor to bring about the perfection of seeming simplicity of the American whip.

I say American whip advisedly, because the result of this evolution of ingenuity has been the production of a type

that is purely national. What is technically known as the "bow" whip is

A RESULT OF YANKEE THOUGHT

and it is pre-eminently the whip of this country.

An Englishman, German, Spaniard, indeed, any foreigner, requires a shrub, a bit of rawhide, a knife and patience and he can produce a goad of one sort or another to suit his fancy or needs. The more highly organized mechanical faculty of the American, to produce a whip to his liking, demands a whale, a ship and sailors to hunt it, the gut of the cat, a rattan jungle in India, a hickory grove in his native country, a cotton plantation, mulberry trees and silk worms, a forest of rubber trees, the hide of the buck, fossil gum from Africa, linseed oil, iron, paint, the art of the turner and designer in metal, the tusks of the elephant, gold, silver and various alloys, the hoofs of animals, the product of the Ilax field, precious stones, the genius of the mechanic in the invention of strange and novel machinery,

THE ACUTEST BUSINESS AND EXECUTIVE ABILITY;

then he goes to work to produce that simple article of trade—a whip!

When put upon the market it can he bought for twenty-five cents, or you can run to the extremes of luxury that are represented by hundreds of dollars, but the essential principle of manufacture is the same in either case.

Burns wrote his immortal verse on a plain deal table; Seneca extolled the blessings of poverty, preparing his argument on a solid gold table. The means used to produce the expression did not modify the genius in either case. The whip costing a dollar will last as long, produce as stinging a blow, and be as useful an instrument in conveying your sentiments to the cuticle of the animal, as one costing a hundred times as much.

It would appear, then, that the manufacture of a whip is a very interesting process, well worthy of investigation. Let us look into it.

To do this thoroughly and understandingly it is necessary to journey to a small town in western Massachusetts, Westfield by name, that is

THE CRADLE OF THE INDUSTRY,

and to-day stands forth without a rival in all the world as the whip center.

Here we see a flourishing town, whose chief and practically whose only industry is the making of whips.

It has no parallel that we know of in this or any country in the civilized world.

And this great business has all been evolved in so short a time as that which elapsed between the year 1808 and the present! In this connection we quote from a trade periodical a little of the history of the early years. It reads:

At this time (1808) there lived in Westfield a man named JOSEPH JOKES, Who happened to become the owner of a choice lot of hickory. His many friends frequently called on him to be obliged with a piece of this wood for whipstocks, whips being then home made. Finally Jokes made some of these stocks and offered them for sale. A little later he conceived the idea of putting a lash on the stock. The lash consisted of a heavy strip of horsehide, which was made fast to the stock by a ‘keeper,’ and thus we have the first whip made in Westfield.

Jokes did quite a business, and

OTHER MEN BEGAN IMPROVING ON THE STOCK

The Automatic Bounder.

|

by boiling the wood in a preparation of oil and coloring. The recipes for making these preparations were secrets among those who made whips, so each one had a preparation of his own; but some were much better than others.

Five years later lashes were made, by narrow strips of raw, horse or cowhide, and plaited into cords, very much the same as at present. A piece of leather, rolled round and beveled, to make the swell, was inclosed in the center. The lash was rolled between blocks, and then varnished. In 1820 the experiment of plaiting a covering of cotton thread over the stocks was tried, hut was only partially successful, as it was done entirely by hand, holding the stock on the knees.

At this time different materials began to be used for stocks; rattan, and the best of all for the purpose, whalebone.

WHEN WHALEBONE WAS FIRST BROUGHT INTO USE

the entire stock was made of it, a thing rarely afforded at the present time. Whalebone is now used in manufacturing the drop, on account of its tenacity. After some degree of completeness had been acquired in plaiting Over the stock, an attempt, with success, was made to bring into use the drop whip, which, of course, was only a combination of stock and lash, and covered the entire length, thus dispensing with the ‘keeper.’ This was a decided improvement, and many whips, in a small way and slow process, were made and offered for sale.

About 1822 an invention was brought into use for whip plaiting by Hiram Hull, father of an ex-president of the American Whip Company at Westfield. Mr. Hull was the first man to start what could well be called a factory, when this invention was used. It resembled a barrel in appearance from its shape, and was also called a barrel. The whip to be covered was suspended by the top, and hung down in the Center of the barrel. A number of threads were attached to the top of the whip, and hung over the edge of the barrel, with weights to keep them in position. These weights Were worked by the hand, throwing them in opposite directions, thus

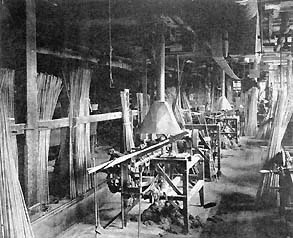

The Old Fashioned Plaiting Machine.

|

PLAITING THE WHIP

almost as perfectly as at the present time, though the process was a very slow one. This invention Was in use through a number of years, and an expert at working it was looked upon as a good tradesman. Women are said to have attained quite a speed in working the threads with their nimble fingers. The process is shown in the engraving entitled ‘The old-fashioned plaiting machine.’

The plaiting of to-day is made on the same principle as the one just described.

The drop whip passed through quite a number of years unmolested; then the drop began to decrease, and finally a whip was made perfectly straight, and took the name of the bow, or the trotting whip; thus the three kinds of whips were in use that are now, viz. Whips with lash and keeper, drop whips, and bow or trotters’ whips.

*Adapted from "Harness" (trade magazine), New York. Engravings made expressly for this work.

© Laurel O’Donnell 1996 - 2006, all rights reserved

This document may be downloaded for personal non-commercial use only

and may not be reproduced or distributed without permission in any format.

This is an edited adaptation from the original publication.

|