When at last the wheels of the big press begin to turn, the rush and push against the iron railing is two-hundred-boy power. There is a two-hundred-boy force to the yell that is raised for papers at the same time. "Gimme twenty!" "I want sixty!" "forty!" and the pennies go over the railing as fast as the man behind can take them. Perhaps that sharp boy with the funny shock of hair, who is squeezed firm in front of the mass, hands over a loaded fifty cent piece and cries out, "Fifty papers!" He expects a good quarter besides in change, but he rarely gets it. The man in charge knows his business as well as he knows the boys, and leaded pieces and plugged coins have to be taken back.

One boy gets his bundle of damp papers, there is a squeezing through an almost impossible space that couldn’t be seen a moment before and is closed over the next moment, and the boy is abroad with the news. There is a rush for the first street man, and then off for stores, factories and lounging places. All is business.

One little fellow who lisps, "I’m doin’ to sell all my papers if I stay out till eight o’tlock," is full of energy, and, as well, polite. When his pockets don’t hold the change for nickels, he runs to the nearest store and gets it, and when someone tells him to keep the change, he is prettily thankful. That is the boy who, at six, earns a dollar a week towards his bank-book. He has not yet been to school, but knows how to master his money problems. He began his work on a sound basis with a few papers, and little by little added customers, until at the end of a twelve-month he takes out forty papers every day.

Another little fellow, not so honest or industrious, and not so successful, for that matter, but cuter and more schemy, covers his face with dirt, makes it look as if he had been crying, and

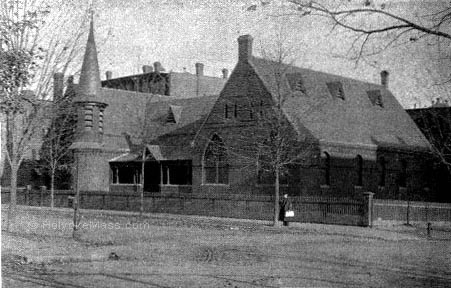

Unitarian Church.

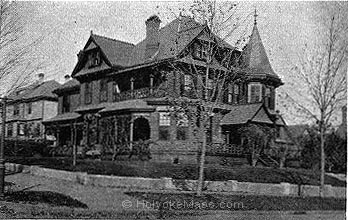

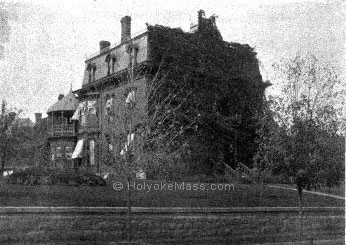

Residence of James Ramage.

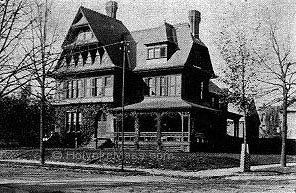

Residence of E.W. Chapin.

|

|

tries the sympathy of guests at hotels. His frail and poorly clothed figure is the last on the streets at night, and he is never afraid to appeal to the stranger’s kindheartedness. If he is cold, or hungry, or dirty, with him that is a matter of business; the look of suffering or pain or hardship has a money value. Because he likes the work, this other little fellow sells a dozen papers, rain or shine, while that big boy is out only when the weather favors. He is a high school lad, for whom selling papers means not so much business as spending money.

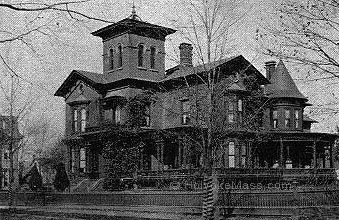

Residence of E.C. Taft.

Residence of William Skinner.

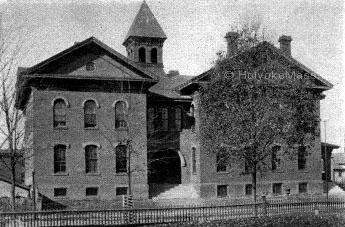

Appleton Street School.

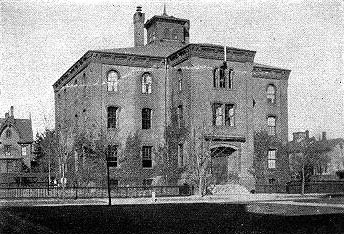

The High School.

|

Still another schemer is the boy who has "only one paper left," and won’t sell it for less than two cents because he "will have to cut some one," and rather than do that he says he will pay double price himself. But no sooner has he made this sale and is on the other side of a crossing, than a paper appears and is ready for the next buyer. Still the scheming is an exception. In the main, it is an honest crowd that sells the news to its readers, crying long from sheltered doorways, "Only a cent, Mister, for Holyoke daily papers."

|