The Road Down from the Park.

|

Mount Holyoke, From the Park.

|

Well, then, is there no chance for you? Yes; there is a splendid chance, if you will only seize it. There have been those from your very class who have won success. They had your disadvantages, but they have made men of themselves—successful, worthy, influential gentlemen. All honor to them! What they have done, you can do.

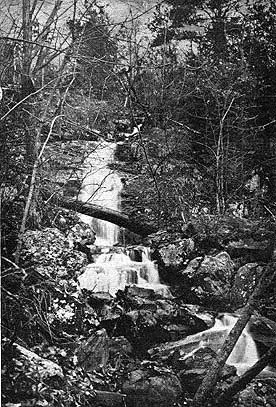

Mount Tom Brook.

|

Can anything be done to give the boys in the city a better chance?

Yes; there are some things that can be done, and that must be done. Our system of education must be modified so as to provide industrial as well as mental training. The education of the hands, the education of the eye, the education of the judgement, the education of the will, that a boy gets by learning to work, are of more consequence in the future life than arithmetic and geography and grammar. These last are of great importance, but those first are of greater importance; and it is a poor system of education that makes no provision for them.

It is habits rather than methods of industry, however, that you need to learn; and many of you will find some opportunity of learning these about your own homes if you will look for them. There is considerable work of one kind or another that boys can do—that some boys do—in connection with the house, or the garden, or the grounds; and if you will shoulder this, and do it well and faithfully, the exercise and the training will be very profitable to you, and may be very helpful to your parents.

Furthermore, there is plenty of chance for you to do faithful mental work; and this, if you will take hold of it with a will, may be almost as valuable training for future usefulness as manual labor could be.

To begin with—there is your every-day school work, to which some of you might give a great deal more time, with great profit. If you will take the studies that you like least, and go at them with the determination to master them—if you will put yourself right down to the disagreeable parts of your school work with steady patience, and hold yourself to them till they are thoroughly done—you will get, in such victories as these, a discipline of will that is almost as good as you would get in hoeing a stony potato field. Besides, there are lines of reading and study that you could take up in connection with your school work, in which you would find the best kind of discipline. If the boy who now spends almost all his afternoons in the park, or visiting boy friends, and almost all his evenings at his club, or at the music hall, and who fills in the intervals of leisure with Fireside Library stories, will make up his mind to give

Song of the Mountain

|

Far from their mountain home my streams

Wander and leave me to my dreams;

Singing they go

To the sea below,

And leave me to my dreams.

Once, from my arms they could not stray;

Helpless, but safe, they cradled lay

Clasped in my arms,

Secure from harms,

Nor wished for me to stray.

Now from my sheltering care they roam,

Seeking below a fairer home.

Ever be nigh

Oh, gracious sky,

Where’er my dreams may roam.

|

Sun, moon and stars my wanderers guard;

Cheer all their way;—their tasks are hard,

The way is long,

They are not strong,—

Watch o’er them, guide and guard.

Come, fleetest night-winds, speed away,

A message bear for me, I pray,

To far off sea—

Where’er they be —

My children, far away.

Carry my love, lest they forget

Old days at home with me,—and yet

Forbear to chide,—

The world is wide,

And busy hearts forget.

|

Gather their kindest thoughts of me,

Wrap in a cloud that waits by the sea,

And in my dreams

My wandering streams

Shall come and comfort me.

— John Howard Jewett.

|

|

|

at least two solid hours of every day to the reading of some instructive book—doing it of his own accord, doing it thoroughly, not fooling around two hours with the book in his hand, but holding his attention right to it, whether he is specially interested in it, or not, till he comprehends it and fixes it in his mind—that will prove to him a most valuable training.

The boy who can do a thing like this can make a man of himself. He is not the kind of chap that will be elbowed off the track by country boys, nor by anyone else.

Of course you ought to have a chance to play, and a schoolboy needs to play. I should wish my boys to have at least two hours every day of good, wholesome, vigorous outdoor sport. So much as that would not hurt them, I am sure—though that is a great deal more than I had. But I am equally sure that all those city boys who really expect to hold their own in the great competitions of the world, must give less time to idleness, and play, and foolish reading, and put their minds and their wills in training for the serious work of life.

© Laurel O’Donnell 1996 - 2006, all rights reserved

This document may be downloaded for personal non-commercial use only

and may not be reproduced or distributed without permission in any format.

This is an edited adaptation from the original publication.

|