He must be a good deal of a barbarian in these days who has no use for writing paper. He is at any rate an object of pity; for he must either be sadly lacking in education, or a man who has no friends and no business. It might be affirmed with considerable truth, that civilization itself rests on our ability to produce paper cheaply and in large quantities. What could our printing presses do without it? If books could not be made at moderate cost, education would be again confined to the few instead of as now being the heritage of the great majority. One’s circle of friends would narrow, too, for if we could not write, from ignorance or because of the expense, we would lose sight and thought of many and they of us. Those who lack education, as a class, live in mists of prejudices and superstition. Education is a light which puts darkness to flight, and it is often made in the pictured simile of an old lamp or a torch. To keep this flame burning was a fight against great odds in the old days, when learning was guarded by a few scattered groups of monks or some little handful or patricians of this or that empire, which had gained temporary prominence and power. It was like a pyramid resting on its point with the base in the air. Permanent safety could only come by bringing it down on the base of a general education and a continual interchange of ideas. This state the development of the paper-making industry has been an important factor in bringing about. War itself is affrighted and slinks away, for it only thrives in the glooms of ignorance, with its accompanying prejudice and hasty anger. It would be interesting to watch the development of paper making from its first primitive beginnings up to the present, but in the space of this article there is only room to describe the process as is in one of the modern great mills of the present.

The chief ingredient of fine writing paper is rags. Added to this is a small percent of wood pulp. Newspapers are often made almost wholly of wood pulp, but this material has not the strength and fiber to make the finer grades. Rags are in the first place gathered by the street scavengers before mentioned, or by their more aristocratic cousins who have possessed themselves of a cart, and in some cases of a horse to draw it. Such gather the rags of our cities and the regions neighboring. In the more distant country districts, though the old-time Yankee tin peddler is no more, his somewhat degenerate prototype still makes occasional rounds and trades tinware and other varied necessities of the kitchen economy for the contents of the housewife’s bags of rags and feathers. However the rags are gathered, they all in time find their way to some dealer who sorts and bales them and then sells them to the mills. Many of the rags come from the Old World countries across the Atlantic. No doubt enough rags are produced in this country to supply the demand, but at the price they bring many will not take the trouble to save them.

Let us enter a paper mill, and look about. I suppose we will find ourselves in the office in the first place and there see rows of desks and various clerks and bookkeepers, who scratch away with their pens very much after the manner of their class anywhere. But get permission to go through the mill. There are the great brown bales of rags weighing from six to nine hundred pounds each, and here are heavy paper-wrapped bundles of wood pulp. Reach into one and pull forth a piece Why! it’s not pulp but paper — a very heavy, coarse-textured white paper. But that is the shape in which it reaches the mills and it must be ground over again to make an article for the public. It seems a wonder that this white pulp paper could have been made out of the yellow spruce wood, which is the material out of which it is largely made at present.

The lower floors of this part of the mill are mostly given up to storage. We mount to the fourth story. Here the bundles of rags are being slashed open by a man with a big knife; the brown sacking and cords are removed, and the close-packed mass is pulled to pieces and thrown into a great hopper. There a swiftly revolving wheel catches the rags on its spikes and whirls them about so fiercely that you wonder to find any rags left after the process, to say nothing of getting the dust out of them.

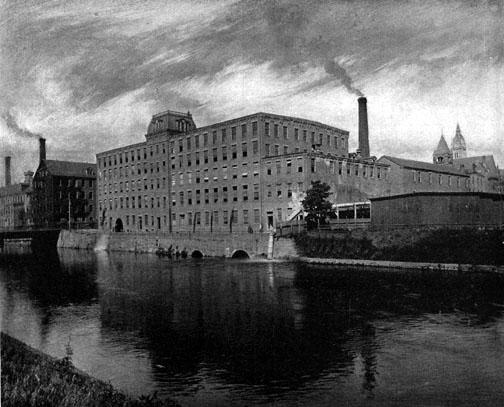

No. 2 Mill of the Whiting Paper Company, Holyoke.

© Laurel O’Donnell 1996 - 2006, all rights reserved

This document may be downloaded for personal non-commercial use only

and may not be reproduced or distributed without permission in any format.

This is an edited adaptation from the original publication.

|