A Visitor and Her Dog.

A Peddler — Oliver Street.

After A Snowstorm.

Sidewalk Sliding.

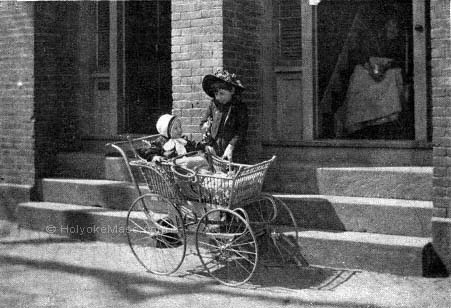

Playing with the Baby.

|

On the Corpus Christi Festival Catholics love to make their church altars beautiful for the placing of the sacred Host. They drape the altar shelvings with rich laces, hang soft curtains on statues, and place everywhere lighted candles. Flowers, too, are everywhere, to make for this day, given to the worship of the body of Christ, one of the most beautiful of the Church observances.

In 1875, on Thursday, the 27th of May, just when the year was most delightful, the French people of Holyoke were gathered in their church for the Corpus Christi vesper service. The church was small and poorly built — a frame structure, sheathed to the ceiling, with no plastering to make it firm or heavy. At best it was only a temporary house of worship, built so that these many people, who spoke a strange tongue, might have the gospel preached to them in their own language. Up to five years before they had worshipped with the old St. Jerome society, but they had gathered in numbers and wealth enough to have their own church and pastor, and Rev. A. B. Dufresne had been sent to them for a religious guide. Under his supervision the little church was begun on the first of December 1869, and by New Year’s day was ready for service, with just one month’s work upon it. Meanwhile, the parish grew and a fine enw church was going up near by, substantial and well built.

On that warm May night there were six hundred people at the vesper service—a large crowd for the building, that seated only eight hundred. There was to be confirmation in the church next Sunday, and many children and young people who were praying for the rite sat in the low, narrow galleries that ran around the building. It may have been a breeze from a near window, or some say it was the swaying of a woman’s fan that floated the light lace draped over the Virgin’s statue too near the lighted candle on the pedestal. In an instant the bit of fire had leaped up the draping. Some of the men who were close by tried to put it out, but the flame was too quick for them. It licked up the curtain and swept on to the thin sheathing, and the building was doomed.

All thought then was for safety — for escape with life and friends. From below there was a mad rush for the main door in front, and most of the people got safely out. But up in that crowded gallery, only eight feet above the floor, were the hundreds of young people who, from three sides of the building, had but one way of escape, and that a narrow four foot stairway. It could not be the exit for that panic-stricken crowd. People who saw tell of such a rush that where the stairway ended was a mass of people so wedged together that they no longer seemed living beings. Without were ready helpers, but with that packed mass blocking the doorway, the work of rescue was terribly slow, and the heat and smoke did their work almost unchecked.

A young fireman on a baseball field nearby, who a few years later became Chief Lynch of the fire department and one of the most skilled firemen in the state, was one of the first to reach the fatally crowded doorway. He pulled forth body after body, this one dead and that one alive, even if the conditions were exactly the same. It is a triumph to save one life, and to save many lives, as did the firemen and some of the men who were in the burning church, must forever make the rescuers men marked among other men.

|