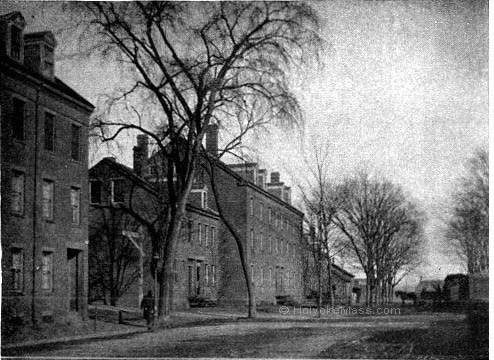

Front Street.

|

"Oh, de ghos’, de ghos’!" he howled. "I seen him! I seen him!"

There was plenty of superstitious fear in the spool-room, and the word that Andre, too, had seen the ghost passed around in a shuddering whisper. There was no stampede toward the hall this time, for the overseer was on hand and he had a stern voice and a stern eye.

He lifted the shivering bobbin boy by the collar and gave him a shake that tended to restore his scattered wits.

"What do you mean by such nonsense?" he asked sharply. "You go back down stairs where you belong, and don’t you come up here again to raise such a screeching as that."

Poor Andre! He was in hard luck, for when he had sent the bobbin box spinning across the hall, it had hit and upset one of the tall oil cans standing against the wall and the yarn on the bobbins was soaked and spoiled. The quaking lad had to go down and report the accident to his own overseer, who cuffed him for his carelessness and threatened to discharge him if such a thing happened again.

A week or two passed by and the spool-room ghost had become the talk of the mill. The scrub woman and the bobbin boy had to listen to much sly jesting, but there were many who were disposed to look upon it as a serious matter. The smaller spoolgirls especially showed an earnest avoidance of the elevator hall as soon as the shadows of evening fell, and when they were obliged to go for their cloaks and hats at closing hour they took care to go in the strength of numbers, and to make as brief a stop in the hall as possible.

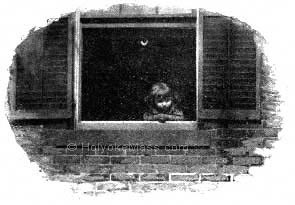

A Front Street Cherub.

|

The talk quieted down at last, and when one night two or three of the warper girls found themselves left the last ones in the spool-room after the speed had stopped, they were thinking nothing about the ghost as they went toward the cloakroom.

It was Katie Crippen and Maggie Hayes and Julia Pray who were in the cloakroom together hurrying on their wraps, when suddenly a fearful specter rose before them in the corner. Through the darkness it showed weird and white and ghastly. Over a sheeted form rose the semblance of a face gleaming with a strange, unearthly light, and as it made a movement forward the girls shrieked with horror and ran.

They did not stop until they had reached the bottom of the last flight of stairs, and had pushed the door open and were out in the open air. They were all quite hysterical with terror, but there were no signs of pursuit, and they safely reached home.

The story went about the mill the next morning, and there was a set expression on the overseer’s face as he proceeded to a thorough investigation of the hall and cloakroom. But nothing unusual was found. There was a long closet, with shelves, on one side of the hall, where the girls stored their hats, and a row of hooks beyond where they hung their cloaks and shawls. The closet extended up nearly to the ceiling. Back of the elevator was a long sink built solid to the floor. No apparent hiding place for a ghost-player was there.

For a long time after this there was no further alarm. The winter wore away and spring came, and at last the days had grown so long that gas light was no longer needed. On the first day that the speed went down on the unlighted room, the ghost made its final appearance.

One of the smaller spoolgirls saw it. Once more a terrified shriek rang from the cloakroom and the child came rushing out pale with fright.

The employes, now released from duty by the stopping of the speed, crowded into the hall and the overseer followed.

Training the Dog in the Way he Should Go.

|

The foremost of the crowd heard the sound of something like a sudden rush or scramble, but nothing was to be seen but the closed closet and the row of shawls and capes hanging on the wall.. The window was open, but no one could have escaped by an opening ful forty feet above the ground.

"I’ll get a long stick, and if the ghost is in any corner of this hall we’ll poke him out of his hole," said Hugh Brett.

Two or three of the girls gave a little scream.

"Oh, ye needn’t be scared, girls," said Hugh. "The ghost will be the one to do the squealing when we find him."

The overseer threw down the shawls and cloaks to see if anything was concealed behind them. Hugh armed himself with a window pole and began to explore the closet.

There was nothing on the top. It must, indeed, have been a shadowy ghost which could have hidden itself in that narrow space. The opened closet showed the girls’ hats and hoods piled in some confusion on the shelves.

"Nothing here? — wait a bit," said the Scotchman.

Under the lowest shelf, rolled into a corner that would have been cramped quarters for a medium-sized dog, was something that looked like a ball of white cloth. Hugh reached down and gave it a tug.

"If that wasn’t a live boy’s foot I got hold of, then I’m not a Scotchman," said Hugh. Taking a firmer grasp, the bundle was jerked out upon the floor.

Then from the folds of a large spread of white cotton, such as was used to cover the warps when the mill shut down on Saturday, was slowly unwound the crest-fallen figure of Sandy Hutton — Sandy, his shamed face still showing in the dim light the brimsonte marks he had not had the time to remove. He had played his roguish prank just one time too many.

So the ghost of the spool-room walked no more, for Sandy’s place in the mill instantly became vacant, and next day the spool-room of No. 2 had a new spoolboy.

© Laurel O’Donnell 1996 - 2006, all rights reserved

This document may be downloaded for personal non-commercial use only

and may not be reproduced or distributed without permission in any format.

This is an edited adaptation from the original publication.

|